How Permaculture Can Help Answer Global Crises

Published September 22, 2020 in West of Wild, By Keri Haugse

In the middle of a global pandemic, raging wildfires, and public outcry over systemic inequalities, the call to reform our food system—the building blocks of community health and resilience—is louder than ever. The converging crises of climate change, resource depletion, and political instability lead many of us to look for a system of what CAN work in uncertain times.

Permaculture is one system that seeks to provide practical solutions for the question of how human civilization can live successfully on the earth without depleting natural resources.

A blend of the words agriculture and permanent, permaculture can be described as an integrated design system, or more broadly, a system of ethics focusing on “taking care of the land, taking care of the people, and sharing the abundance.”

By moving beyond the realm of land use and into economic and political territory, permaculture differentiates itself from the simplicity of regenerative agriculture or organic farming. It combines the tools and techniques of ancient cultures with whole-system design strategies in order to create living, evolving systems in which each member plays a respected role. The goal is to provide mutual benefit to the land, the people, and the community as a whole.

Permaculture is one system that seeks to provide practical solutions for the question of how human civilization can live successfully on the earth without depleting natural resources.

A blend of the words agriculture and permanent, permaculture can be described as an integrated design system, or more broadly, a system of ethics focusing on “taking care of the land, taking care of the people, and sharing the abundance.”

By moving beyond the realm of land use and into economic and political territory, permaculture differentiates itself from the simplicity of regenerative agriculture or organic farming. It combines the tools and techniques of ancient cultures with whole-system design strategies in order to create living, evolving systems in which each member plays a respected role. The goal is to provide mutual benefit to the land, the people, and the community as a whole.

The Beginning of the Permaculture Movement

Turning their back on industrial agriculture and the commercial food industry in the 1970’s, a professor at the University of Tasmania, Bill Mollison, and his student, David Holmgren, began developing the framework for an agricultural system that mimics the functioning of our planet’s natural ecosystems. In 1978, the pair released a book titled Permaculture One and the term permaculture was officially coined in print.

Doug Bullock, another leader in the permaculture movement, has been designing human habitats, eco-villages, and intentional communities for over forty years. In a 2015 interview, Bullock spoke on the potential for permaculture to help “re-indigenize” the world’s populations by observing our own environments and asking how we can create the highest use of our landscapes. He noted that both people who live in cities and those who live in rural landscapes live a definitively urban lifestyle—buying packaged food and materials from the store, utterly disconnected from its source. In a prescient comment, Bullock noted it would take extreme stress and hardship (I.e. food shortages, electricity shortages, or fuel shortages) for people to make the transition to a more sustainable lifestyle: “Before that [hardship happens], I doubt it”.

Five years since Bullock’s interview was recorded, we find ourselves stressed. Seeing the effects of climate change in the wildfires ravishing the American West, record temperatures, storms, and droughts, many people are looking for a way to change our relationship to the natural world.

But all hope is not lost. There are few among us who have decided to dedicate their lives to the sustainable production of food; the simultaneous capture of carbon; and a return to harmony with the planet we call home.

The Practice of Permaculture

Permaculture is being practiced at this very moment: in a seaweed farm off the coast of Hawaii; a food forest garden in the Canary Islands, and on tiny plots of land throughout the United States where those seeking to ‘do more’ have enrolled in hands-on Permaculture courses.

Beth McCormick, artist and founder of the Permaculture Foundation of Hawaii, was once one of the latter.

Turning their back on industrial agriculture and the commercial food industry in the 1970’s, a professor at the University of Tasmania, Bill Mollison, and his student, David Holmgren, began developing the framework for an agricultural system that mimics the functioning of our planet’s natural ecosystems. In 1978, the pair released a book titled Permaculture One and the term permaculture was officially coined in print.

Doug Bullock, another leader in the permaculture movement, has been designing human habitats, eco-villages, and intentional communities for over forty years. In a 2015 interview, Bullock spoke on the potential for permaculture to help “re-indigenize” the world’s populations by observing our own environments and asking how we can create the highest use of our landscapes. He noted that both people who live in cities and those who live in rural landscapes live a definitively urban lifestyle—buying packaged food and materials from the store, utterly disconnected from its source. In a prescient comment, Bullock noted it would take extreme stress and hardship (I.e. food shortages, electricity shortages, or fuel shortages) for people to make the transition to a more sustainable lifestyle: “Before that [hardship happens], I doubt it”.

Five years since Bullock’s interview was recorded, we find ourselves stressed. Seeing the effects of climate change in the wildfires ravishing the American West, record temperatures, storms, and droughts, many people are looking for a way to change our relationship to the natural world.

But all hope is not lost. There are few among us who have decided to dedicate their lives to the sustainable production of food; the simultaneous capture of carbon; and a return to harmony with the planet we call home.

The Practice of Permaculture

Permaculture is being practiced at this very moment: in a seaweed farm off the coast of Hawaii; a food forest garden in the Canary Islands, and on tiny plots of land throughout the United States where those seeking to ‘do more’ have enrolled in hands-on Permaculture courses.

Beth McCormick, artist and founder of the Permaculture Foundation of Hawaii, was once one of the latter.

|

After coming across a quote by Aldo Leopold (reprinted below), her decision to take environmental action “wasn’t a question at that point, it was a necessity”.

Aldo Leopold: The Cost of An Ecological Education “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.” Aldo Leopold, The Cost of An Ecological Education |

Refusing to deny the reality of industry at all costs, McCormick started where we’re all capable of starting, by making a commitment to “radically consume less.”

As consuming less necessarily requires creating more, McCormick enrolled in a permaculture course under the tutelage of Bullock and learned how to grow her own food.

As consuming less necessarily requires creating more, McCormick enrolled in a permaculture course under the tutelage of Bullock and learned how to grow her own food.

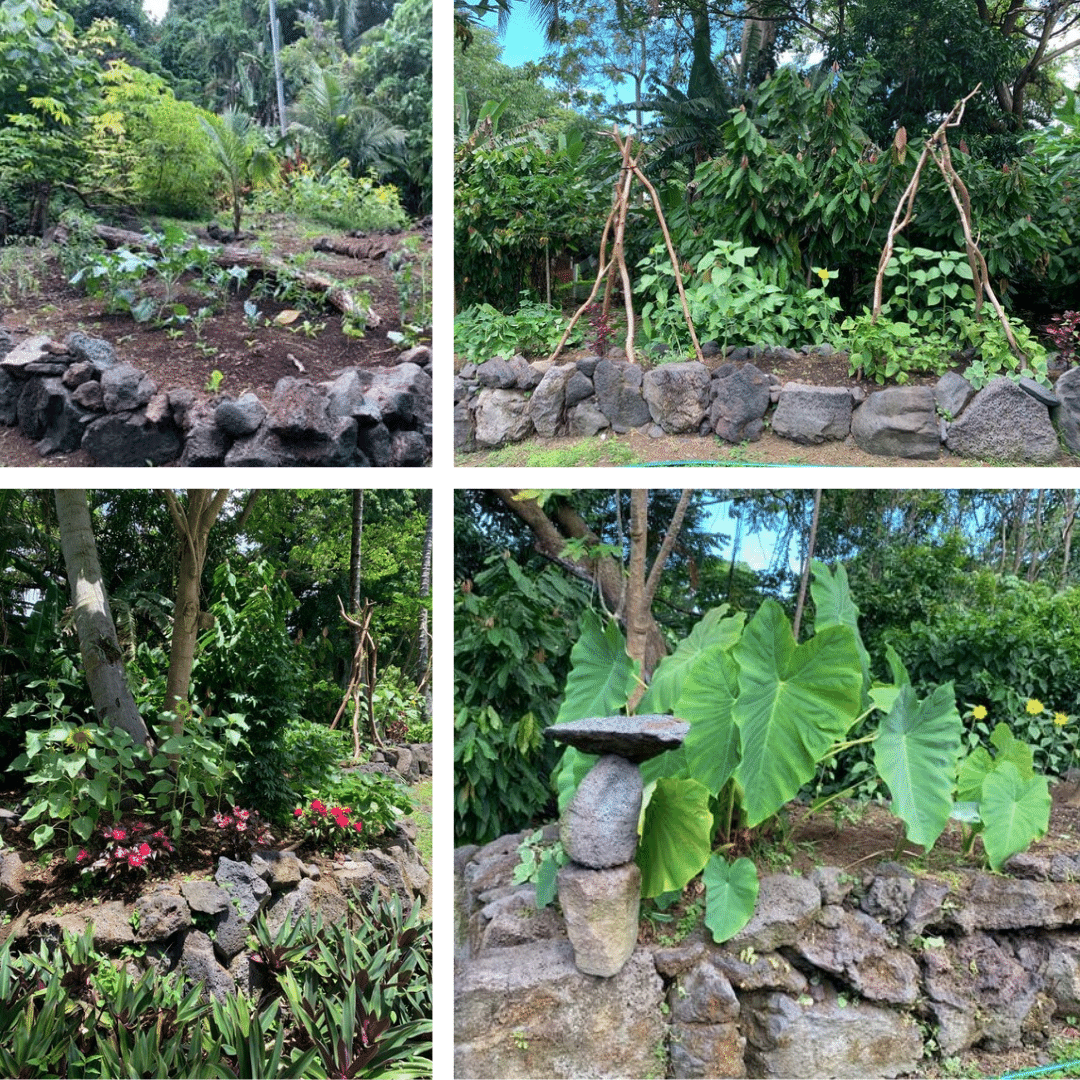

Starting with a three acre plot of land in Opihikao—on the irrepressibly wild east side of Hawaii Island—she ventured into the unknown. On this land, McCormick uncovered fruit bearing plants that had been thriving unassisted for fifty years. Coconuts, bananas, coffee, avocado, mango, guava, and breadfruit grew in abundance, impeded only by the invasive species McCormick and her partner began to clear away.

Letting Nature Lead The Way

In Opihikao, McCormick discovered that human intervention is not necessary to produce a bounty of nutritious produce, once a food forest is established. Likewise, a foundational principle of permaculture is to let nature do the work for you. It requires the farmer to observe first and make changes second. The choice of what to plant is determined by what wants to grow in a particular environment, and there is much more diversity than typical monoculture.

McCormick soon realized that permaculture was an “excellent way to grow food” because, “once it’s planted, it doesn’t require the 10 calories [of input] for every 1 calorie on the plate that [commercial] agriculture does.” The principal caveat being that these types of farms don’t produce the high yield of fruits and vegetables that commercial farms do. Thus, it’s up to consumers to decide if they’re willing to consume less, but more nutritious fruits and vegetables. In order for permaculture to be commercially viable, consumers have to be “willing to pay a little bit more for things that are done the right way”.

Twenty years after the founding of the off-grid Anawaiwela Farm, you can find the same coconut, banana, avocado, and ulu trees that have been thriving in Opihikao for decades. Now they grow intertwined with a wide variety of citrus, mango, ginger, and cacao trees planted by the couple. “It’s basically a chocolate farm. That’s what we planted the most of.

Letting Nature Lead The Way

In Opihikao, McCormick discovered that human intervention is not necessary to produce a bounty of nutritious produce, once a food forest is established. Likewise, a foundational principle of permaculture is to let nature do the work for you. It requires the farmer to observe first and make changes second. The choice of what to plant is determined by what wants to grow in a particular environment, and there is much more diversity than typical monoculture.

McCormick soon realized that permaculture was an “excellent way to grow food” because, “once it’s planted, it doesn’t require the 10 calories [of input] for every 1 calorie on the plate that [commercial] agriculture does.” The principal caveat being that these types of farms don’t produce the high yield of fruits and vegetables that commercial farms do. Thus, it’s up to consumers to decide if they’re willing to consume less, but more nutritious fruits and vegetables. In order for permaculture to be commercially viable, consumers have to be “willing to pay a little bit more for things that are done the right way”.

Twenty years after the founding of the off-grid Anawaiwela Farm, you can find the same coconut, banana, avocado, and ulu trees that have been thriving in Opihikao for decades. Now they grow intertwined with a wide variety of citrus, mango, ginger, and cacao trees planted by the couple. “It’s basically a chocolate farm. That’s what we planted the most of.

Off-grid Anawaiwela Farm, Opihikao, Hawaii

Looking To The Past To Move Forward

The plants McCormick initially discovered growing wild in Opihikao are known in the islands as canoe plants—brought to Hawaii in the hulls of outrigger canoes steered by Polynesian voyagers.

“When the Hawaiians first got here, there was very little to eat. The Hawaiians brought with them a couple dozen plants including coconut trees, breadfruit, sweet potatoes, taro, bananas, and ti-leaf. These plants were enough to sustain a civilization.”

Beth McCormick

McCormick explains that permaculture has a tradition of looking back to what has worked sustainably overtime and notes that Polynesian Polyculture is a star example of what a sustainable food system could look like. Yet, even back then, when everything on the island was cultivated for the utmost productivity, McCormick notes that the Hawaiians navigated back and forth from Polynesia and continued to trade. She remarks that, “No man is an island” and the ancient Hawaiian’s understood trading as a form of abundance.

Art, Meditation, & Mythology

Art is another way that McCormick trades ideas with the world. Like permaculture, she sees art not as a formal set of design principles, but rather, as “a way of moving through the world”. Like the act of farming, she notes that art is self-healing, self-centering, and can be used as a meditation device—stripping away our individual egos to reveal our common humanity:

“If you look at mythology from all over the world, you see the same stories of heroism and challenges—times in someone’s life when the world turns upside down and they don’t know whether they’re going to survive. They have to go deep within themselves to find the perseverance to meet that moment. Collectively, that’s what we’re all going through right now.

Within this pandemic, that conflict is happening and we’re going through it together as a species.”

Thus, you could say we’re at the point where it’s a fool’s errand to play the role of the ostrich in Leopold’s warning by making believe “that the consequences of science are none of [one’s] business”. Yet, if you’ve played the role of the ostrich before, or know a few ostriches, it’s still possible that as a society we will emerge from our current hardships on the side of greater collective awareness.

McCormick notes that:

“Planet earth tends to have darkness and light side by side. It’s hard to look at any institution or any era, and say that ‘that was a Golden Age’ and ‘that was all light’. Because if you really look, there was a shadow in all of these times. Part of the challenge of being a human is to live in this world of dark and light and act with as much consciousness and as much awareness as possible.

“I believe the answers are not individual, they are collective and that’s going to take political action.”

How You Can Take Political Action

The plants McCormick initially discovered growing wild in Opihikao are known in the islands as canoe plants—brought to Hawaii in the hulls of outrigger canoes steered by Polynesian voyagers.

“When the Hawaiians first got here, there was very little to eat. The Hawaiians brought with them a couple dozen plants including coconut trees, breadfruit, sweet potatoes, taro, bananas, and ti-leaf. These plants were enough to sustain a civilization.”

Beth McCormick

McCormick explains that permaculture has a tradition of looking back to what has worked sustainably overtime and notes that Polynesian Polyculture is a star example of what a sustainable food system could look like. Yet, even back then, when everything on the island was cultivated for the utmost productivity, McCormick notes that the Hawaiians navigated back and forth from Polynesia and continued to trade. She remarks that, “No man is an island” and the ancient Hawaiian’s understood trading as a form of abundance.

Art, Meditation, & Mythology

Art is another way that McCormick trades ideas with the world. Like permaculture, she sees art not as a formal set of design principles, but rather, as “a way of moving through the world”. Like the act of farming, she notes that art is self-healing, self-centering, and can be used as a meditation device—stripping away our individual egos to reveal our common humanity:

“If you look at mythology from all over the world, you see the same stories of heroism and challenges—times in someone’s life when the world turns upside down and they don’t know whether they’re going to survive. They have to go deep within themselves to find the perseverance to meet that moment. Collectively, that’s what we’re all going through right now.

Within this pandemic, that conflict is happening and we’re going through it together as a species.”

Thus, you could say we’re at the point where it’s a fool’s errand to play the role of the ostrich in Leopold’s warning by making believe “that the consequences of science are none of [one’s] business”. Yet, if you’ve played the role of the ostrich before, or know a few ostriches, it’s still possible that as a society we will emerge from our current hardships on the side of greater collective awareness.

McCormick notes that:

“Planet earth tends to have darkness and light side by side. It’s hard to look at any institution or any era, and say that ‘that was a Golden Age’ and ‘that was all light’. Because if you really look, there was a shadow in all of these times. Part of the challenge of being a human is to live in this world of dark and light and act with as much consciousness and as much awareness as possible.

“I believe the answers are not individual, they are collective and that’s going to take political action.”

How You Can Take Political Action

- Vote. Registering to vote and voting is the most fundamental way to use your power as a citizen of the United States.

- Register to be a poll worker. McCormick notes that volunteering as a poll worker in your local community is one of the best ways to get involved. You might even make a little bit of money.

- Read about the candidates in your area and educate yourself as to what’s possible. Local elections and your elected officials have the biggest direct impact on your community. Know who you want wielding that kind of power before you go to the polls.

- Join a group that is taking care of a piece of land: a park, a vacant lot, or a community garden.

- Buy food from your local farmers markets.

- Consume Less: buy fewer, better quality things.